Equity and Climate in the Built Environment

Climate change and social inequality are two of the most pressing challenges of our time. These are global issues that are complex, systemic, and entangled.

Their negative consequences have been felt for decades, but they are becoming more acute and severe each day, particularly for marginalised communities in urban areas. The built environment – the places where we live, work, and interact with others – has a defining influence over our ability to live healthy, fulfilling lives. Cities are where 70% of global carbon is emitted and where people experience the most severe impacts of climate change, rising living costs, and socio-economic inequalities. It is also where these global challenges can be addressed, showing the important and inextricable link between local and global dynamics.

In all regions of the world, policymakers, planners, developers, real estate investors, engineers, architects, and construction companies are developing a range of policies and financial investments to reduce carbon emissions and address the climate crisis. However, the impacts of climate actions, like the impacts of climate change, are not felt equally by everyone. For example, policies like mandating the use of bio-based materials, introducing subsidies for building retrofits, or replacing leaky buildings with energy-efficient ones may all have positive environmental impacts. However, if they are not accompanied by purposeful strategies and mechanisms to equitably distribute the benefits they seek to generate, they may inadvertently exacerbate inequality between landlords and tenants, residents of different neighbourhoods, and different workers. Communities that feel left behind are likely to push back against these climate initiatives, which may result in further delays and roadblocks.

Despite such challenges, climate actions can and must be inclusive. Government- or business-supported climate initiatives that acknowledge existing inequalities within and between communities can address environmental issues while also fostering social inclusion and respect for human rights. Socially and environmentally sustainable models and paradigms are possible. They require concerted efforts and ongoing commitments to participatory processes, a shared responsibility for results, and accountability for adverse impacts on individuals and communities.

This way, the built environment sector can fulfil its critical role in helping address climate change and, concurrently, in reducing social inequalities.

Defining Just Transition

While there is no universally accepted definition of the term just transition, the concept was pioneered by the trade union movement and is considered today by the International Labour Organization (ILO) to entail “greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities, and leaving no one behind."

It is key that just transitions processes include social dialogue, social protection and the recognition of labour rights. This means workers (and also local communities) should have agency and should be legitimate counterparts to governments and businesses.

For the purpose of this project, just transitions refer to climate actions that:

Are ecologically-conscious as well as supportive of societal development within planetary boundaries, and;

Ensure the benefits of such shifts are equally spread and enjoyed, and that costs are not borne by traditionally excluded or marginalised groups.

From an IHRB perspective, a just transition should include four essential elements:

Preventing risks and adverse impacts;

Equal access to opportunities and benefits;

Accountability to, and agency of, potentially affected groups; and

Transformational systems change.

Just transitions are intrinsically context-specific and efforts to implement related strategies in various sectors continue to evolve. For the purpose of this project, a human rights framework was used to assess the social impacts of climate action in the built environment.

Human rights: four thematic areas

This project, and IHRB’s wider Built Environment Programme, aims to make human rights part of everyday business by drawing attention to existing international standards and commitments, and detailing how these should inform the processes that shape the built environment around the world.

These include standards relating to the realisation of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ESCR) such as the right to housing and access to health services, as well as to a healthy environment, workers’ rights, and land-related rights. The work of the programme and this project also include a focus on civil and political rights, particularly non-discrimination, and procedural rights, including the right to meaningful participation in decision-making processes.

With this human rights grounding, the project researched how transition processes in eight cities are being planned or taking place with regards to four thematic areas:

Workers' rights

Freedom of association and collective bargaining, social dialogue in transition processes, no forced or child labour, no discrimination, and a safe and healthy working environment, to apply on site and throughout supply chains.

Right to housing

"The right to live in a home in peace, security, and dignity, which includes security of tenure, availability of services, affordability, habitability, accessibility, appropriate location, and cultural adequacy”.

Spatial Justice

Refers to the principles of equality and non-discrimination applied to space. Spatial justice is defined as “fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to use them”, and an even development, free of biases imposed on certain populations because of their geographical location.

Participation

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights recognises the right to participate in public affairs. This UN-recognised right to participation, when applied to the built environment, relates to the concept of the right to the city proposed by philosopher Henri Lefebvre who argues people should be able to take part in, appropriate, and shape the built environment they inhabit and use. Therefore, it is “not merely a right of access to what already exists, but a right to change it”.

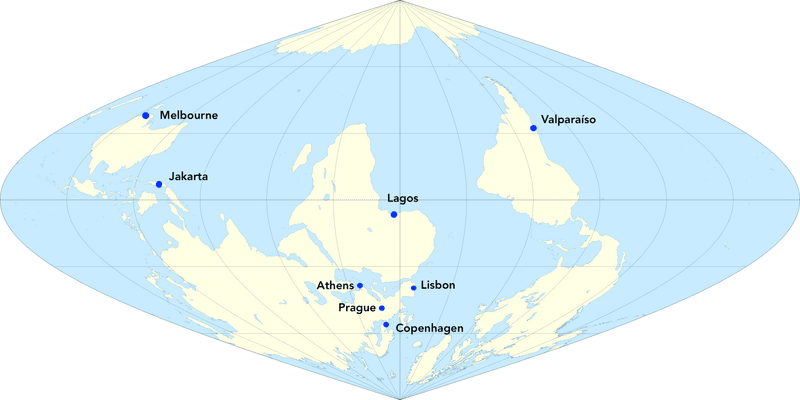

The eight cities selected as case studies were: Lagos (Nigeria), Prague (Czechia), Lisbon (Portugal), Melbourne (Australia), Copenhagen (Denmark), Jakarta (Indonesia), Valparaíso (Chile), and Athens (Greece).

Project overview and research design

This report summarises the results of the two-year action research project Building for Today and the Future: Advancing a just transition in the built environment. The project's main goal was to open up pathways for ecological transitions in the built environment that are equitable, inclusive, and just. It did so through the following objectives.

Action research: investigated climate actions taking place in the built environment in the eight cities and identified positive and negative impacts on people, power relations in decision-making, and proposed what can be done differently.

Land ownership: mapped the major private and public landowners in the four European cities as a step to increase transparency and accountability.

Economic innovation: identified examples of emerging innovations that aim to address root causes of inequality and climate degradation.

Visioning workshops: Brought together a large diversity of stakeholders in each of the eight cities, including governments, businesses, trade unions, tenant organisations, NGOs, academia and other civil society organisations. Actors workshopped their visions for their cities’ future sustainable and just built environment. These sessions also helped strengthen local narratives for green and equitable transitions.

Findings from the research and visioning processes informed policy advocacy and communications at the European and global level, and yielded strategic recommendations, guidance documents, and tools dedicated to:

Local governments: City Toolkit: The role of local government in advancing a just transition in the built environment

Investors: Making the case for green and affordable housing investment in Europe

Worker representatives: Future green construction jobs: skills and decent working conditions

Academia and future generations: Course on human rights in the built environment

Research Questions

The project posed the following Research Questions (RQ) in each of the eight cities:

To what extent are climate actions in the built environment considering human rights? How do local climate policy and actions reflect and consider the basic needs of inhabitants?

Who are the key actors, and who is shaping decision-making?

What are the positive and negative impacts on people, including different communities?

How are these impacts distributed throughout the city?

What are the political conditions that allow or hinder a just transition in the built environment?

What are the linkages (or lack thereof) between environmental and socially sustainable developments?

What are the current enablers and the barriers to a just transition?

What are the linkages to relevant national and international processes?

Is the current government willing and able to uphold human rights in climate policies?

How can we build in a way that does not contribute to climate change, strengthens resilience, and benefits everyone regardless of income, ability, gender, race, or age? What innovative models, strategies, or initiatives are emerging to move towards a more just transition?

What is the vision of stakeholders for a just transition?

What is necessary and feasible to reach that vision?

How and why are innovative models, strategies, or initiatives providing better social and environmental outcomes?

Research Methodology

The subjects of study in this project were the challenges and opportunities for the incorporation of human rights into the ecological transition of the built environment.

Transition processes included the relevant policies and actions underway in each city (decarbonisation policies, building renovations, and circular economy projects), as well as relevant national processes (climate commitments or adaptation plans), and the relationships, actions, and limitations of built environment stakeholders.

To carry out this global research over a period of two years, IHRB staff were supported by independent, local researchers (see Acknowledgements for a full list of the research teams) contracted for 3-4 months in each city. The research employed qualitative research methods, including field visits, observation at local events, semi-structured interviews with stakeholders from different sectors, and a visioning workshop.

The eight cities were selected to ensure diversity in:

Location: four cities in Europe with a geographic spread within the continent and one city on each of the other continents, with a focus on coastal cities given their greater vulnerability to climate change.

Contexts: a wide range of characteristics, including: population, urban extension, city’s contribution to global emissions, as well as different political, social, and economic spheres deriving from path dependencies and resulting in different local priorities.

Built environment decarbonisation processes: a mix of cities with more- and less-developed climate policies and initiatives allowing comparative analyses of their impact on human rights.

Acknowledgements

Cite as: Institute for Human Rights and Business, “Advancing Just Transitions in the Built Environment: A global research project exploring human rights in the green transition” (June 2024), available at https://www.ihrb.org

Attribution: Primary author: Alejandra Rivera, IHRB Built Environment Global Programme Manager

Important contributions from:

Giulio Ferrini, IHRB Head of Built Environment

Marta Ribera Carbó, IHRB Europe Programme Manager

Comments on the report were provided by:

Scott Jerbi, IHRB Senior Advisor

Sam Simmons, IHRB Head of Communications

Annabel Short, Principal It’s Material and IHRB research fellow

Local research teams who contributed to this project in independent consulting capacities:

Athens: Liam O’Farrell, Dr Vicky Kaisidou and Dimitrios Tsomokos

Copenhagen: Line Knudsen and Christine Lunde Rasmussen, Ramboll Management Consulting

Jakarta: Dayinta Pinasthika, Citieslab (part of Nusantara Urban Advisory)

Lagos: Oluwafemi Joshua Ojo, Durham University

Lisbon: Diana Soeiro

Melbourne: Joanna Tidy, Lucy Lyon, Natalie Galea, Judy Bush, and Dan Hill, University of Melbourne, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning

Prague: Michaela Pixová, BOKU University of Life Sciences and Natural Resources, Institute of Development Research

Valparaiso: Sebastian Smart, Anglia Ruskin University, and Rodrigo Caimanque and Belen Segura, Universidad de Chile

Special thanks to all 126 people interviewed across the 8 cities and the 203 participants in the 8 visioning workshops. This work would not have been possible without your kind willingness to share your knowledge and contribute to making built environment transitions more just.

Copyright:

© All rights reserved. IHRB permits free reproduction of extracts from any of its publications provided due acknowledgment is given. Requests for permission to reproduce or translate our publications should be addressed to [email protected]