Conclusion

At the outset of the green transition, all studied cities were already facing urban challenges to varying degrees: housing provision and affordability; informality, precariousness, and workers’ rights' breaches in the construction sector; low or unequal access to green spaces, jobs, and opportunities; and low or unequal degrees of participation in city-shaping.

This study found built environment climate actions in all eight cities studied, however, the ecological transition is not happening at the same scale or at the same pace around the world. Drivers and incentives for the transition, and specifically for the decarbonisation of the built environment, vary greatly by city, country, and region.

Some climate actions helped tackle socio-economic issues, while others exacerbated them. The difference: an inclusive and equitable approach.

Initiatives that tackled climate change with an equity lens gained widespread support, attracting further investment. When climate actions were disconnected from inequality issues in the city, this was reflected in the discontent of workers and tenants, in the form of street protests, and government and business leaders’ reputations suffered.

The communities pushing back against decarbonisation are often those whose human rights remain unaddressed and who stand most to lose from the lack of climate action: fFor example, if their homes are leaky and in climate-vulnerable areas, if their jobs rely on dwindling natural resources with no alternatives to transition, or if their voices are not heard. Their further marginalisation risks compromising the political and economic stability that allows governments and businesses to play their role in society.

Cities are at a juncture: they can be reactive to greenlash and end up rolling back climate actions, or they can develop and implement holistic strategies that address both climate and social issues together, thus ensuring future climate initiatives are grounded in equity.

This report discusses each city within its unique geographical, political, and economic context. With the need to identify common trends to galvanise collective action, this conclusion brings together the commonalities identified in the study. This requires the use of terms like ‘global north’ and ‘global south’ which can be reductive but are necessary to highlight underlying global differences. As recognised in Modern Housing: An Environmental Common Good:

While terms like Global North and Global South are gross simplifications, and examples of living environments typically associated with the term Global South can be found within the North and vice versa, it is also possible, and necessary to recognise that these patterns of extraction are highly visible within global flows of material, capital, culture and people themselves, and that the Global North has extracted resources, natural and otherwise, from the Global South to produce its built environment.

There was a clear difference between cities in the Global North (Prague, Lisbon, Athens, Copenhagen, Melbourne) and in the Global South (Lagos, Jakarta, Valparaiso). Global North cities were found to be more advanced in their implementation of decarbonisation initiatives. However, their per capita emission levels remain significantly higher than those in the Global South. While their emissions are reducing, they are amongst the countries that, along with the US and, more recently, China, are disproportionately responsible for climate change.

In the Global South cases of this study, the transition narrative is visible at the country level, with a myriad of international commitments to net zero and national policies, plans, and strategies in place that promise to achieve sustainability. In some cases, these even explicitly mention inclusivity and fairness, showing promising intentions. However, there is a clear gap in their implementation at the local level. It was found that these ambitious national commitments and green pledges do not translate into actionable steps for lower levels of government, contrasting sharply with the realities found on the ground.

This can be explained, in part, by a clear difference in priorities. Global South megacities like Jakarta and Lagos face large-scale, critical, urgent urban problems such as informal settlements, air and water pollution, and lack of public services such as electricity, waste management, and more. Tackling these urban issues is rendered more challenging by shortcomings in governance and civic engagement. Hence, it is difficult to imagine how ambitious national climate plans can be implemented on the ground unless they simultaneously address these basic issues.

Global South cases were found to be more concerned with environmental justice issues, such as the differentiated impact of climate change on local communities, and the impact of industrial activities on their natural environments, for example, the pollution of water streams and nature. In the Global North cases, this study found a greater focus on a just transition, meaning climate actions, their implementation, and their differentiated impacts on people.

As shown in this report, there are multiple risks of not undertaking the green transition in a just and inclusive way, or not undertaking it at all. Delays in climate actions mean most vulnerable communities will continue to experience the negative impacts of climate change, exacerbating inequality and risks to human rights. The large size of cities in the Global South scales both the risks of exacerbating, and the opportunities of addressing, social inequalities through holistic and inclusive climate actions.

European context

The EU’s climate policy has been a key driver of built environment decarbonisation action in the four European cities analysed as part of this study. The EU’s climate goals have led to national climate policies and guided decarbonisation of residential buildings, channelling public and private resources into reducing emissions from the built environment.

Climate action has created opportunities to modernise inefficient and ageing housing stock, increase sustainable and affordable housing, and create employment opportunities in the construction sector. To stay within their carbon budget, EU countries can only build a combined 176,000 residential units per year. Therefore, retrofitting existing homes must be prioritised over building new.

The climate agenda took the EU’s centre stage during the 2019-2024 mandate of the commission, which significantly increased the resources dedicated to climate action. In each of the four European cities researched, this resulted in governments, businesses, and civil society developing and implementing, to varying degrees, initiatives to reduce climate emissions in the built environment.

The extensive investment has resulted in visible (albeit insufficient) progress in decarbonising Europe’s built environment. This creates opportunities to modernise inefficient and ageing housing stock, increase sustainable and affordable housing, and create employment opportunities in the construction sector. Unfortunately, Europe has also been the region where greenlash has been most visible. This results in notable instances of climate policy reversal, with negative consequences for green businesses, which need long-term certainty, as well as for climate targets.

EU investment in climate action must continue, but its next phase must be grounded in equity. A just transition is rooted in the needs of the communities most at risk from climate change. A human rights-led approach to climate action can achieve this goal, particularly by protecting and upholding the right to housing, workers’ rights, participation, and spatial justice.

Roles and responsibilities

The advancement of human rights in societies around the world is complex and therefore a constant and collective endeavour. This includes the right to housing, worker rights, meaningful participation, and spatial equity in the built environment’s green transition.

Since its inception in 1945, the United Nations has been the main international body defining and promoting human rights. Since the second half of the 20th century, human rights have become a fundamental issue for business operations. Rapid globalisation has led to greater international business operations and more complex supply chains, increasing the risk of overlooking responsibilities or systematically violating human rights in countries with weak regulations.

In 2011, the UN’s Human Rights Council unanimously endorsed the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), which set out the roles and responsibilities of governments and businesses in ensuring human rights are protected and respected across all sectors, including the built environment.

The UNGPs are the world’s most authoritative, normative framework guiding responsible business conduct and addressing human rights abuses in business operations and global supply chains.

The UNGPs were field-defining because they clearly stated the duties and responsibilities of States and businesses, and highlighted the need for their complementarity to ensure human rights are upheld. The UNGPs comprise 31 principles organised in three pillars:

Pillar 1: States’ duty to protect

Human rights in the context of business operations. This requires States to set clear expectations for companies by enacting effective policies, legislation, and regulations. In doing so, States establish that appropriate steps are in place to prevent, investigate, punish and redress adverse human rights impacts.

Pillar 2: Corporate responsibility to respect

This pillar outlines how businesses can identify the negative human rights impacts of their business operations, and how to demonstrate that they have adequate policies and procedures to address them. Businesses should also undertake ongoing human rights due diligence to identify, prevent and mitigate human rights abuses.

Pillar 3: Access to Remedy

This pillar stipulates that when a right is violated, victims must have access to effective remedies which are legitimate, accessible, predictable, equitable, transparent and rights compatible. Pillar 3 sets out criteria for effectiveness of judicial and non-judicial grievance mechanisms implemented by both States and businesses.

Applying the UNGPs to the built environment industry, it is evident that every actor has important roles and responsibilities to contribute to the realisation of human rights in the industry. It is also abundantly clear that these rights cannot be upheld without tackling climate change, as extensively evidenced through this research.

Governments from local to national levels, including city councils, regulatory bodies, urban planning departments, public procurement departments, and all public institutions, have the responsibility to use public policy to protect human rights in their built environment.

Businesses, including real estate investors, developers, project owners, small and large architecture, planning, and design firms, construction companies, their respective contractors and sub-contractors, and their business partners throughout the supply chain, all have the responsibility to use their internal policies and business operations to respect human rights in the built environments where they extract, operate, and sell.

Both actors above, governments and businesses operating in the built environment sector, are responsible for providing access to remedy when a human right has been violated. This includes, for example, providing legal and practical solutions and fair compensation to people who have been forcedly evicted from their homes. The right to access remedy also applies in other areas like construction workers’ rights, or spatial discrimination.

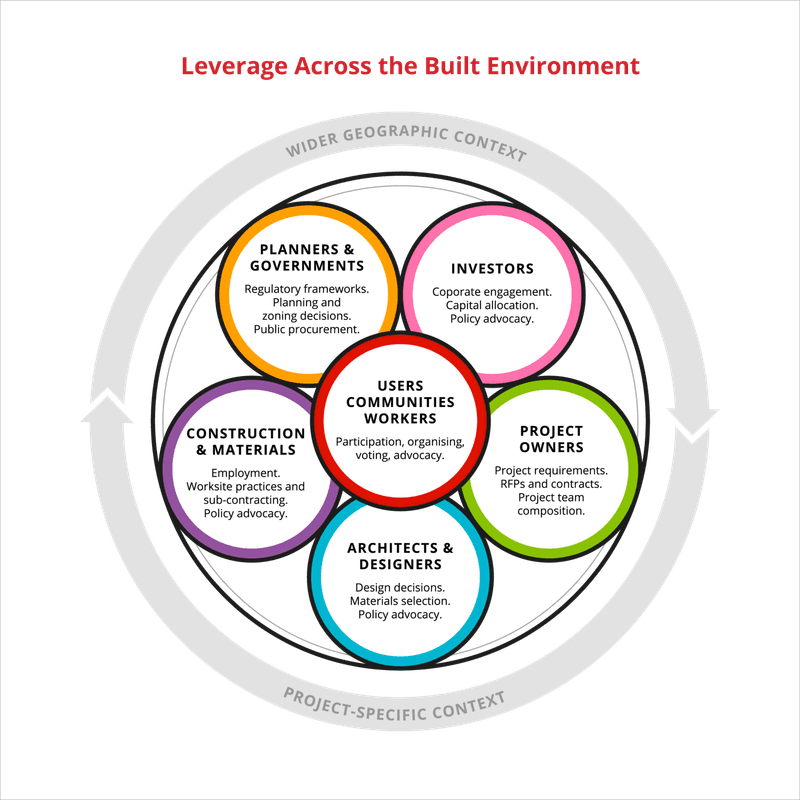

The infographics below summarise the continuum of human rights risks and responsibilities across the built environment lifecycle, the inter-relatedness of the actors, and points of leverage between them. The distribution of power between these actors largely determines the nature of the built environment, and whether it responds only to narrow financial interests or also to the needs of users, communities, and workers, particularly the most vulnerable.

The Built Environment Lifecycle

Recommendations

The following section provides 44 recommendations across the four human rights areas that this research study dives into. These are organised by scope (global or EU only) and directed to either governments, investors or both. Their implementation requires close collaboration between the public and private sectors, as well as meaningful engagement with the communities directly impacted by built environment decisions and climate actions.

This would be possible through mission-oriented stakeholder collaborations that cut across disciplines, sectors, departments, and levels of governance. These holistic collaborations facilitate working together towards the complex, but attainable, goal of a just transition in the built environment.

Recommendations

Filter

decision-maker

geographic-scope

human-right

Towards systems change: Three steering principles

While the recommendations outlined above can provide incremental change towards a just transition, it is necessary to look at the structural and long-term changes necessary for justice to be the norm. A sustainable and just future requires a fundamental reshaping of economies to produce regenerative systems that address unequal power dynamics head on. Hence, to contribute ideas towards systemic change, this report provides three steering principles for governments and investors, and three collective endeavours for all seeking a more just and inclusive world.

Three steering principles for governments and investors

The most important principle is for urban leaders, industry leaders, and finance leaders to have a true and caring commitment of heart and mind to an inclusive and just ecological transition. This means acknowledging that the current linear and extractive economic model is not good for the planet nor for the vast majority of people,; and that the ecological transition to a circular, regenerative, and sustainable model is a political, business, and moral imperative. Commitment in heartset and mindset means having a high degree of honesty with oneself, colleagues, partners, and the wider society, that such transition is difficult, that there are clearly going to be winners and losers, and having the equally compelling political, business, and moral imperative to contribute to making the process more inclusive and just.

It is necessary to change the attitude, the willingness and approach to governance. There is an attitude required to deliver governance: an attitude of humility, of acknowledging power and responsibility as a privilege, which requires you to value individual citizens and motivates you to create policies for citizens.

Tpl. Olutoyin Ayinde

President of the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners (NITP)

Research Interview, October 2022

This study found evidence of human rights being violated or ignored in the built environment and in its green transition. At the same time, it identified a multitude of opportunities and solutions emerging from people committed to a just transition, and willing to contribute from their roles and leverage, but who often have lesser influence and decision-making given the current power relations in the cities. The second steering principle is to educate with objective information, empower with independent tools, and create spaces for the flourishing of the committed. This principle, if followed, has the potential to transform current injustices by opening spaces for innovative ideas, various forms of knowledge, and creative solutions to our current urban pains. The visions and the emerging innovative models exemplify this potential.

Action without vision is only passing time, vision without action is merely daydreaming, but vision with action can change the world.

Nelson Mandela

The third principle is for government, finance and business leaders to embed human rights in their everyday practices. This report adds to the comprehensive evidence demonstrating the negative impacts on productivity, efficiency, stability, and sustainability when human rights are undermined. Specifically, this research shows that climate change is a social issue, and hence that the right to housing, worker rights, spatial justice, and participation need to be upheld to tackle the climate crisis. With this in mind, it proposes a different lens for governing, a different lens for investing: one whereby all transition initiatives have the explicit goal of protecting and respecting human rights, with clear mechanisms in place for transparency, accountability, non-discrimination, and participation.

Housing should not be treated as a commodity like gold or steel [a transactional asset], it is a basic human right to have a place where you have peace, security, and most importantly dignity.

Leilani Farha

Founder and Executive Director of The Shift,

former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing

(paraphrased from public discourse)

Three collective endeavours for all seeking a more just and inclusive world

Prior to the emergence of market economies, economic activities such as farming, barter, and local trade were embedded within their social contexts, and economic value was proportional to their societal contribution. Since the Industrial Revolution, there was a process of steady commodification of everything, including land, labour, and housing, and the development of market-led economies and profit-led behaviour. Karl Polanyi called this a process of disembeddedness, where economic activities became increasingly separated from their social value and environmental considerations. This disembeddedness of the economy becomes particularly problematic when paired with a focus on consumption, economic growth, and its measurement through the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This leads to environmental degradation and growing social inequalities: two of the most pressing global challenges of our time.

Polanyi argues for the re-embedding of the economy within society to address social and environmental challenges effectively. For the purposes of this research study and the interests of its readers, this can be understood as the need to embed social value or respect for human rights (back) into the processes that shape the built environment and into the ecological transition itself. This two-year global research project has identified three global shifts that, if pursued collectively, can enable this re-embedding.

Shift in Value

A just transition in the built environment requires rescuing its social function and rethinking its value beyond its current conception as a commodity, as another transactional asset within market-led economies and subjugated to profit-led behaviour.

The first endeavour is the collective recognition of the value of the built environment as an enabler for human flourishing and, therefore, a shift to valuing its social functions over its price. In cities, the adequate and fair provision of housing, transport infrastructure, urban systems like water and electricity networks, effective urban planning, and fair distribution of natural resources, are what determine the positive or negative conditions of possibility for people’s lives. The building blocks of cities provide the foundation for the quality of life of their inhabitants. Hence, a built environment serving its social functions enables opportunities, whilst a highly-commodified built environment accentuates social inequalities.

The endeavour of rescuing the social value of the built environment requires rethinking what is important for us and how basic, simple, and common it is. Visitors to Jakarta can stay in the penthouse of a five-star hotel, and realise they will not be able to open the window due to the dense fog of brown polluted air on the other side of the glass, and drinking tap water is likely to result in hospitalisation. What are we valuing the most? And is it aligned with our most intrinsic human needs?

From this point of view, the ultimate goal of urban (re)development projects and urban policies should be the optimisation, preservation, and regeneration of natural resources and of their social function. This is not at odds with economic gain, but it should be prioritised and defended besides the latter.

Shift in Narrative

Narratives matter because they influence which ideas are so widely accepted in culture as to have become ‘common sense’.

Mainstream narratives have the power to influence people’s thinking about how the world works and, by extension, how people understand the stories and facts they encounter in daily life. These can be thought of as worldviews, or meta-narratives: beliefs about human nature and how the world works that are built up over time by influential experiences, beliefs, people, and institutions.

There are two important narrative shifts that are necessary as part of this second collective endeavour.

First, while there has been progress on the introduction of environmental sustainability and the need to address climate change in global narratives, the same has not occurred with social sustainability and the imperative to address social injustices, in tandem with climate change. This has only started to change recently, with social dialogue being one of the processes that should be further promoted in shaping new narratives.

Secondly, there is the mainstream perception that the status quo is cemented and immobile. Market-led economies have dominated global narratives for over two centuries longer than any person living today has lived - and therefore have become a generational belief. This might explain the difficulty of imagining a world in which the mainstream value is otherwise, or the struggle of the visioning workshop participants in imagining a just and inclusive future for their cities. It is necessary to embrace an alternative narrative, whereby this future is possible to imagine and to attain.

Shift the Indicator

Lastly, it is necessary to transcend the main indicator used for measuring progress and development, as this speaks clearly of what is valued in that society.

Since the 1930s, GDP has been the most important indicator of economic prosperity, with an increase in GDP seen as the sole thermometer of progress. A singular focus on GDP risks a vehement pursuit of economic growth for the sake of growth, rather than considering this alongside other development indicators.

The third collective endeavour is to move beyond GDP and mainstream alternative indicators to reflect new values and new narratives. As long as the indicator measures only economic value, it will remain challenging to capture and measure social impact or benefit. GDP does not measure fairness, health, happiness, nor quality of life.

Some progress has been made in various places towards alternative, more life-centred (people and planet) indicators, such as the Human Development Index (HDI), Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), Happy Planet Index (HPI), Better Life Index (BLI), Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI) or the Social Progress Index (SPI). Each includes slightly different metrics, some overlapping, some complementary, but none have been globally mainstreamed to the extent the GDP has been for almost a century. Finding collective agreement on a new, post-GDP indicator that focuses on people and planet is a crucial collective endeavour.